By Camila Morales and Alonzo Lepper

The learning contexts and educational experiences of English Learners (ELs) are governed by multiple rules and policies aimed at safeguarding their rights and ensuring equal access to a meaningful education. Many of these guidelines center around ELs’ progress toward attaining English proficiency, helping educators determine who requires English language development support and for how long. This process culminates with a reclassification decision of whether to exit a given student from “English Learner” status. A growing body of evidence links reclassification to future academic outcomes, such as subsequent test scores, high school graduation, and college readiness1Carlson and Knowles, 2016,4Onda and Seyler, 2020,5Pope, 2016

,6Robinson—Cimpian and Thompson, 2016, and points to the importance of setting appropriate benchmarks for determining reclassification decisions.

In this report, we document the evolution of state’s EL reclassification policies since the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) in 2015, a federal law that bolstered states’ accountability toward ELs’ academic progress and mandated the development of uniform statewide procedures for reclassification7U.S. Department of Education, 2016a . We focus our attention on changes regarding test-based criteria: both English Language Proficiency (ELP) assessments and other academic content tests. Our analysis summarizes how the number, kind, and minimum cutoffs associated with test-based reclassification benchmarks vary across states along with changes over time.

As defined by federal guidance, we choose the term “English Learner” to describe students and policies that govern the learning experiences of those whose English language skills affect their ability to participate and succeed in school meaningfully 9U.S. Department of Education, 2017. This choice, relative to alternatives such as multilingual or bilingual students, reflects the fact that most EL students are not taught in bilingual environments nor are they in school contexts that strive for bilingualism2Instructional Models for ELs, n.d.. Therefore, the term “English Learner” more precisely reflects the institutional objectives of most school districts.

This report compares the number, kind, and minimum cutoffs associated with test-based reclassification criteria at three points in time: 2015, 2018, and 2023. Test-based criteria include ELP and non-ELP academic content assessments.

We gathered information about the composition of test-based criteria across states from three sources:

- A survey of EL reclassification policies summarized in a report by Linquanti and coauthors published by the Council of Chief State School Officers, which provided states’ ELP and academic assessment requirements as of 2015.

- A Migration Policy Institute report authored by Villegas and Pompa (2020), which described EL reclassification policies in each state in 2018.

- EL reclassification policy documents on states’ department of education websites, from which we gathered information on EL reclassification policies in each state as of December of 2023.

We computed the number of test-based reclassification criteria by separately adding whether a state requires a summative ELP score, at least one domain-specific ELP score, and at least one academic content assessment. Instances in which a state imposes multiple domain-specific scores (e.g., minimum reading and writing scores) are only counted as having “one” criterion, namely, a domain-specific ELP criteria. This is necessary for consistency in measurement over time given that the information collected in 2015 did not account for the number of domain-specific scores. Moreover, instances in which non-ELP academic assessments are included as part of a range of alternative options, such as grades, GPAs, etc., are counted as “optional” non-ELP criteria.

Lastly, for states with multiple EL reclassification pathways, we documented the policy with the lowest minimum composite score as the most likely pathway faced by students in the state.

Since the passage of ESSA, states have generally lowered the number of test-based criteria required for EL reclassification.

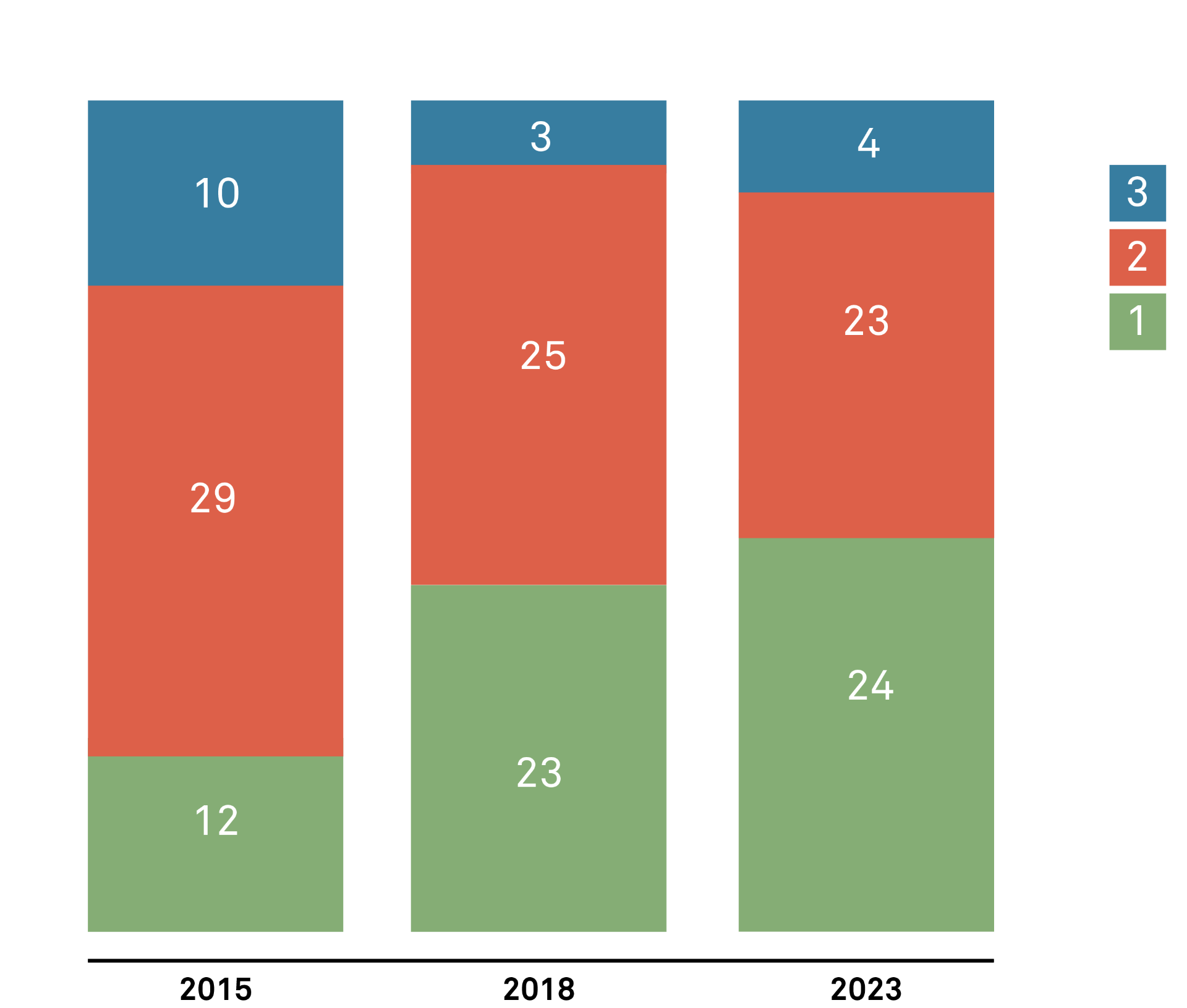

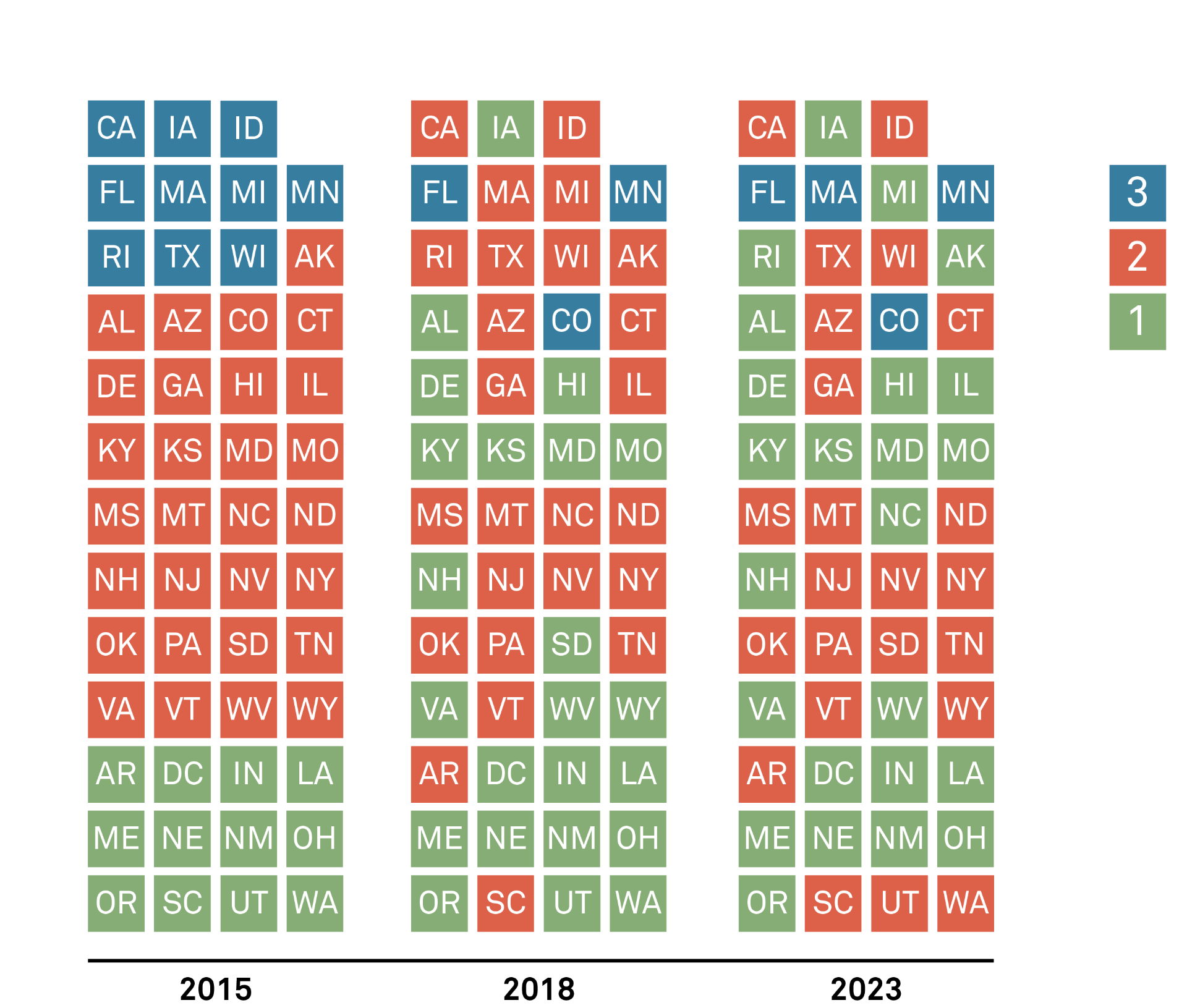

The number of states requiring a single test-based criterion—rather than two or three criteria— doubled from 12 in 2015 to 24 by 2023. Most changes in the number of test-based criteria occurred within three years following the passage of ESSA, which coincides with the time when states were required to submit state education plans to the US Department of Education demonstrating compliance with new mandates, including standardized EL exit criteria 10Villegas and Pompa, 2020.

Among the states that changed the number of test-based criteria required for reclassification from 2015 to 2018, nearly 53 percent (12 states) went from requiring ELs to meet two test-based benchmarks to only one. This group is largely composed of new immigrant destination states, such as Alabama, Delaware, and Maryland, which have experienced relatively rapid growth in their EL student population in recent years. Seven states went from requiring three test-based criteria to requiring two, these include states with large and established EL populations such as California and Texas. Notably, there were also a few states that increased the number of test-based criteria, such as Colorado, which went from two to three test requirements for reclassification between 2015 and 2018.

Fewer changes occurred after the three-year period following the passage of ESSA. Among the 10 states that modified their reclassification policies from 2018 to 2023, half lowered the number of test-based benchmarks from two to one criterion, including Illinois and North Carolina. The remaining five states increased the number of test-based criteria during this same period. Three of these states reverted their initial decrease in test-based criteria. For example, Massachusetts went from three criteria in 2015 to two in 2018, back to three in 2023. States like South Dakota and Wyoming also increased their number of criteria back to two by 2023.

From 2018 – 2023, several states who are members of the WIDA consortium lowered the minimum composite score required for reclassification.

States who participate in the WIDA consortium use the ACCESS 2.0 assessment to monitor ELs’ progress toward English proficiency and make reclassification decisions. ACCESS 2.0 is a standards-reference test measuring language skills across four domains: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. Assessment reports contain domain-specific scores along with summative measures, such as the overall composite score which is a weighted average of the four domains. Assessment results are reported as proficiency scores ranging from 1.0 to 6.0 in 0.1 intervals. Each proficiency level corresponds to a set of proficiency descriptors which anchor a given score to specific skills. For more details, see the ACCESS for ELLs Interpretive Guide for Score Reports.

Since 2017, WIDA adjusted its standard setting which led to an overall increase in the rigor associated with a given proficiency level. Note that this coincides with the timing when several states proceeded to lower their minimum composite score required for reclassification.

Despite fewer policy changes in the aggregate between 2018 and 2023, this period was marked by more subtle variation, such as changes in the minimum composite scored required for reclassification. Among members of the WIDA consortium, for example, the average minimum composite score required for reclassification decreased by nearly 0.25 proficiency points. The modal score also dropped from 5.0 in 2018 (18 out of 36 states) to 4.5 by 2023 (9 out of 37 states).

With the general shift toward lower minimum composite scores among WIDA participating states, there is less variation in cut scores as of 2023 than there was in 2018. However, there is also a more even distribution of states across multiple cut scores. In other words, fewer states are concentrated across a small number of cut scores. For example, in 2018, 50 percent of the WIDA participating states had a cut score of 5.0. By 2023, there was no longer a majority group, but a plurality of states centering at 4.5 (25 percent of WIDA states).

Remarkably, there is still substantial variation in what defines “English proficiency” even among states that follow the same ELP assessment. For instance, North Carolina’s minimum composite score is a 4.8 while neighboring Georgia maintains a minimum score of 4.3. It is also notable that while most states lowered their minimum composite score over time, Tennessee and Michigan stand as outliers experiencing score increases from 2018 to 2023.

Despite overall trends towards simplifying reclassification policies and lowering minimum composite scores, there remain substantial differences in the number and kind of test-based criteria across states.

A plurality of states (47 percent) uses a single ELP test-based criterion for reclassification purposes. Some examples include: Delaware, Michigan, New Mexico, Rhode Island, and Virginia. Most of these states employ a single composite measure across language domains or impose minimum requirements for each domain separately. The latter is particularly the case among states using the ELPA21 assessment, which defines proficiency as a minimum score across all domains rather than a composite measure, as with the ACCESS 2.0 test.

Another common approach is to require multiple ELP test-based criteria, such as a minimum composite score along with imposing a minimum score in at least one language domain, for example reading or writing. This policy structure is used among 9 states (nearly 18 percent), including Arizona, South Carolina, and Tennessee.

The remaining states impose ELP and non-ELP test-based criteria as part of their reclassification policies. Among these, a few require academic assessments as additional tools to assess ELs’ progress toward English proficiency. Typically, these include minimum scores in statewide reading or English Language Arts tests. States in this group include Florida, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and Texas. The state of Nevada, which also requires non-ELP assessments for reclassification, is an outlier in this group as it imposes a minimum score in English Language Arts and math tests as part of their alternative pathway with the lowest minimum composite score. Notably, this policy parameter goes against federal guidance which asks states to avoid using non-language assessments to inform reclassification decisions 8US Department of Education, 2016b.

Lastly, of the 18 states that consider non-ELP assessments, 11 consider non-ELP academic assessments for reclassification as one option among a suite of alternatives such as class grades and grade point average. States with optional non-ELP assessments as part of their reclassification policies include Arkansas, California, Georgia, and Wisconsin.

Since the passage of ESSA, states have generally simplified their EL reclassification policies by decreasing the number of test-based criteria.

Among those that use a common ELP assessment, such as those participating in the WIDA consortium, there has been a trend toward lowering the minimum composite score required for reclassification. As of 2023, roughly half of states impose a single test-based benchmark for reclassification, most commonly a composite ELP score, and only four states require three test-based criteria – a combination of ELP and non-ELP assessments.

However, there remain substantial differences in the number, kind, and minimum ELP scores across states.

This variation reflects both the degree of independence each state has in determining their EL reclassification policies and the lack of centralized guidance around what English language proficiency means and how it’s demonstrated.

Ultimately, whether these differences in policy are a cause for concern depends on the extent to which they serve the learning needs of EL students. What, then, is the optimal reclassification policy for states to adopt? While this question is beyond the scope of our initial work, it is clear that the impacts of reclassification – whether it is beneficial or harmful to academic achievement, or if it provides a smooth transition from EL to former EL status – are directly governed by the set of criteria under which the reclassification decision is made6Robinson—Cimpian and Thompson, 2016. Therefore, establishing appropriate reclassification policies is crucial to facilitate a smooth transition from EL to former EL status. Research points to adverse learning outcomes associated with inadequate reclassification determination where both being reclassified too late or too early result in lost opportunities to learn 6Robinson—Cimpian and Thompson, 2016. Despite the critical importance of optimal reclassification policy selection, both in theory and practice, there is no consensus as to the number, kind, or minimum cut scores defining the notion of English proficiency.

- Carlson, D., & Knowles, J. E. (2016). The effect of English language learner reclassification on student ACT scores, high school graduation, and postsecondary enrollment: Regression discontinuity evidence from Wisconsin. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 35(3), 559-586.

- Instructional Models for ELs. (n.d.). New America.

- Linquanti, R., Cook, H. G., Bailey, A. L., & MacDonald, R. (2016). Moving toward a more common definition of English learner: Collected guidance for states and multi-state assessment consortia. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers.

- Onda, M., & Seyler, E. (2020). English learners reclassification and academic achievement: Evidence from Minnesota. Economics of Education Review, 79, 102043.

- Pope, N. G. (2016). The marginal effect of K-12 English language development programs: Evidence from Los Angeles schools.Economics of Education Review, 53, 311-328.

- Robinson—Cimpian, J. P., & Thompson, K. D. (2016). The effects of changing test—based policies for reclassifying English learners.Journal of Policy Analysis and Management,35(2), 279-305.

- U.S. Department of Education. (2016a). Non-regulatory guidance: English learners and Title III of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

- U.S. Department of Education. (2016b). Addendum to September 23, 2016 Non-Regulatory Guidance: English Learners and Title III of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as Amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

- U.S. Department of Education. (2017). U.S. Department of Education Policy Directive to Ensure Meaningful Access to Federally Conducted Services, Programs and Activities for Individuals with Limited English Proficiency.

- Villegas, L., & Pompa, D. (2020). The patchy landscape of state English learner policies under ESSA. Migration Policy Institute.